Posted: April 12th, 2018 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: interactive audio, sound design, theory

![Want a challenge? Try to play back interface sounds on the show floor at CES. [Intel Booth, CES 2012.]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-03.jpg)

Want a challenge? Try to play back interface sounds on the show floor at CES. [Intel Booth, CES 2012.]

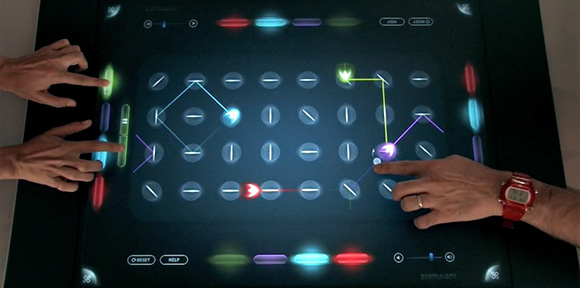

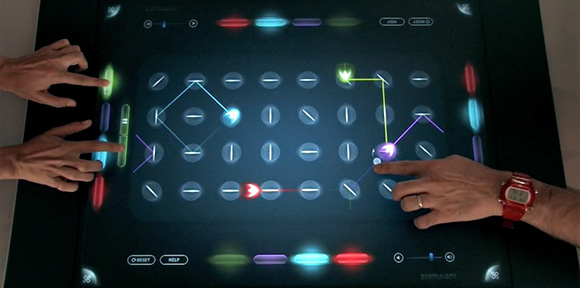

For those that might not know, for the last decade I earned my livingÂ

designing digital installations: Multi-touch interactive walls, interactive projection mapping, gestural interfaces for museum exhibits, that sort of thing. Sometimes these things have sound, other times they don’t. When these digital experiences are sonified, regardless of whether they are imparting information in a corporate lobby or being entertaining inside of a museum, clients always want something musical over something abstract, something tonal over something mechanical or atonal.

In my experience, there are several reasons for this. [All photos in this post are projects that I creative-directed and created sound for while I was the Design Director of Stimulant.]

Expectations and Existing Devices

It’s what people expect out of computing devices. The computing devices that surround me almost all use musical tones for feedback or information, from the Roomba to the XBox to Windows to my microwave. It could be synthesized waveforms or audio-file playback, depending on the device, but the “language” of computing interfaces in the real world have been primarily musical, or at least tonal/chromatic. This winds up being a client expectation, even though the things I design tend not to look like any computer one uses at home or work.

Yes, I strapped wireless lavs to my Roomba. The things I do for science.

Devices all around us also use musical tropes for positive and negative message conveyance. From Roombas to Samsung dishwashers, tones rising in pitch within a major key or resolving to a 3rd, 5th, or full octave are used to convey positive status or a message of success. Falling tones within a minor key or resolving to odd intervals are used to convey negative status or a message of failure. These cues, of course, are entirely culture-specific, but they’re used with great frequency.

The only times I’ve ever heard non-musical, actually annoying sound is very much on purpose and always to indicate extremely dire situations. The home fire alarm is maybe the ultimate example, as are klaxons at military or utility installations. Trying to save lives is when you need people’s attention above all else. However, even excessive use of such techniques can lead to change blindness, which is deep topic for another day. Do you really want a nuclear engineer to turn a warning sound off because it triggers too often?

The Problem with Science Fiction

Science fiction interface sounds often don’t translate well into real world usage.

![This prototype "factory of the future" had to have its sound design elevated over the sounds of compressors and feeders to ensure zero defects. [GlaxoSmithKline, London, England]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-05.jpg)

This prototype “factory of the future” had to have its sound design elevated over the sounds of compressors and feeders to ensure zero defects…and had to not annoy machine operators, day in and day out. [GlaxoSmithKline, London, England]

My day job has been inexorably linked to science fiction: The visions of computing devices and interfaces that are shown in films like

Blade Runner,

The Matrix,

Minority Report,

Oblivion, Â

Iron Man, and even televisions shows like

CSI set the stage for what our culture (i.e., my client) sees as future-thinking interface design. (There’s even

a book about this topic.) People think transparent screens look cool, when in reality they’re a cinematic conceit so that we can see more of the actors, their emotions, and their movement. These are not real devices – they, and the sounds they make, are props to support a story.

Audio for these cinematic interfaces – what Mark Coleran termed FUI, or Fantasy User Interfaces – may be atonal or abstract so that it doesn’t fight with the musical soundtrack of the film. If such designs are musical, they’re more about timbres than pitch, more Autechre than Arvo Part. This just isn’t a consideration in most real-world scenarios.

Listener Fatigue

Digital installations are not always destinations unto themselves. They are often located in places of transition, like lobbies or hallways.

I’ve designed several digital experiences for lobbies, and there’s always one group of stakeholders that I need to be aware of, but my own clients don’t bring to the table: The front desk and/or security staff. They’re the only people who need to live with this thing all day, every day, unlike visitors or other employees who’ll be with a lobby touchwall for only a few moments during the day. Make these lobby workers annoyed and you’ll be guaranteed that all sound will be turned off. They’ll unplug the audio interface from the PC powering the installation, or turn the PC volume to zero.

![This lobby installation started with abstract chirps, bloops, and blurps, but became quite musical after the client felt the sci-fi sounds were far too alienating. [Quintiles corporate lobby, Raleigh NC]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-01.jpg)

This lobby installation started with abstract chirps, bloops, and blurps, but became quite musical after the client felt the sci-fi sounds were far too alienating. Many randomized variations of sounds were created to lessen listener fatigue. There was also one sound channel per screen, across five screens. [Quintiles corporate lobby, Raleigh NC]

Music tends to be less fatiguing than atonal sound effects, in my experience, and triggers parts of the brain that evoke emotions rather than instinctual reactions (in ways that neuroscience is still struggling to understand). But more specifically, sounds with without harsh transients and with relatively slow attacks are more calming.

Randomized and parameterized/procedural sounds really help with listener fatigue as well. If you’re in game audio, the tools used in first- and third-person games to vary footsteps and gunshots are incredibly important to creating everyday sounds that don’t get stale and annoying.

The Environment

Another reality is that our digital experiences are often installed in acoustically bright spaces, and technical sounding effects with sharp transients can really bounce around untreated spaces…especially since many corporate lobbies are multi-story interior atriums! A grab bag of ideas have evolved from years of designing sounds for such environments.

![This installation had no sound at all, despite our best attempts and deepest desires. The environment was too tall, too acoustically bright, and too loud. Sometimes it just doesn't work. [Genentech, South San Francisco, CA]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-04.jpg)

This installation had no sound at all, despite our best attempts and deepest desires. The environment was too tall, too acoustically bright, and too loud. Sometimes it just doesn’t work. [Genentech, South San Francisco, CA]

Many clients ask for directional speakers, which comes with three big caveats. First, they are never as directional as the specification indicate. A few work well, but many don’t, so caveat emptor (they also come with mounting challenges). Second, their frequency response graphs look like broken combs, partially a factor of how they work, and so you can’t expect smooth reproduction of all sound. Finally, most are tuned to the human voice, so of course musical sound reproduction is not only compromised sonically, but anything lower than 1 kHz starts to bleed out of the specified sound cone. That’s physics, anyway – not much will stop low-frequency sound waves except large air gaps with insulation on both sides.

The only consistently effective trick I’ve found for creating sounds that punch through significant background noise is rising or falling pitch, which lends itself nicely to musical tones that ascend or descend. Most background noise tends to be pretty steady-state, so this can help a sound punch through the environmental “mix.”

One cool trick is to sample the room tone and make the sounds in the same key as the ambient fundamental – it might not be a formal scale, but the intervals will literally be in harmony with one another.

Broadband background noise can often mask other sounds, making them harder to hear. In fact, having the audio masked by background noise if you’re not right in front of the installation itself might be a really good idea. I did a corporate lobby project where there was an always-running water feature right behind the installation we created; since it was basically a white noise generator, it completely masked the interface’s audio for passersby, keeping the security desk staff much happier and not being intrusive into the sonic landscape for the casual visitor or the everyday employee.

Music, Music Everywhere

Of course, sometimes an installation is meant to actually create music! This was the first interactive multi-user instrument for Microsoft Surface, a grid sequencer that let up to four people play music.

These considerations require equal parts composition and sound design, and a pinch of human-centered design and empathy. It’s a fun challenge, different than sound design for traditional linear media, which usually focuses on being strictly representative or on re-contextualized sounds recorded from the real world. Listen to devices around you in real life and see if you notice the frequency (pun intended) with which musical interface sounds are commonplace. If you have experiences and lessons from doing this type of work yourself, please share in the comments below.

Tags: music, sci-fi, sound design, sound effects | No Comments »

Posted: June 8th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music

The Stylophone, as most readers of this blog probably know, is a musical toy made famous by David Bowie’s use of it in the track Space Oddity. I own one but honestly, it’s kind of hard to play, and even harder to fit into a mix. Playing evenly with a stylus takes practice and its tones are harsh and nasal.

But it’s 2014. Anything can be made to sound like anything.

I picked up a Korg Mini Kaoss Pad 2 on a whim, and like Korg’s Volca and Monotron range, it’s not great…but it’s an amazing value for the price. What it lacks in configurability and customization it makes up for in expressiveness, immediacy, and convenience. In playing with its onboard loopers – especially the Overdub Looper effect – I realized that I’d never heard Stylophones playing chords. Something new to try…

So, bear with me on how today’s piece came about. The Stylophone’s leftmost tone switch position gives some low-end growl below the E key, and recording it via the headphone out smooths the sound, compared to miking the tiny onboard speaker. I set the MiniKaoss Pad’s Overdub Looper to a certain BPM and build a series of chords on the Stylophone, and used the Mini Kaoss Pad 2’s ability to record directly to an onboard microSD card. The loop points are obvious but intentional and rhythmic, creating an interesting sound, not unlike the Samplr snippet I posted a few months back.

Then I ran that through Michael Norris‘ Spectral Blur plugin to make a hazy, dreamlike wash that communicated what I wanted. Everything else then fell into place, including a TR-606 run through a vintage mono cassette deck, my beloved BugBrand DRM-1, and one of my favorite software synths, TAL Bassline 101.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/209445429″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: looping, music, music 2014, sampling | No Comments »

Posted: January 19th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music, synthesis

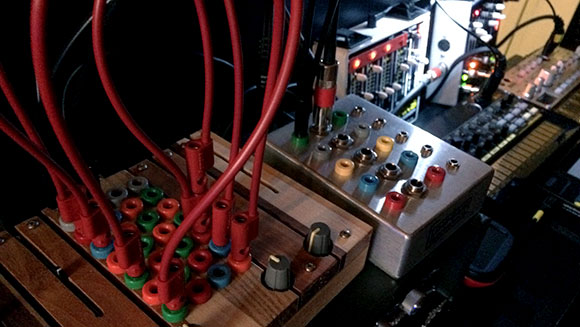

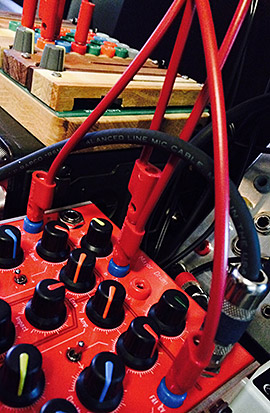

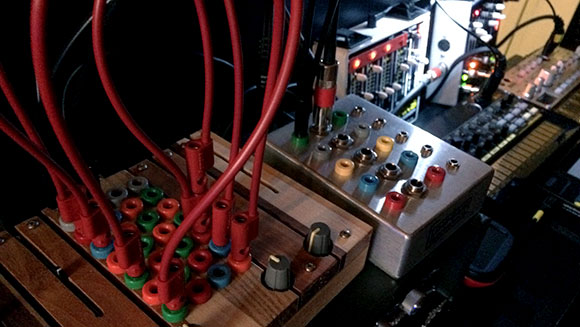

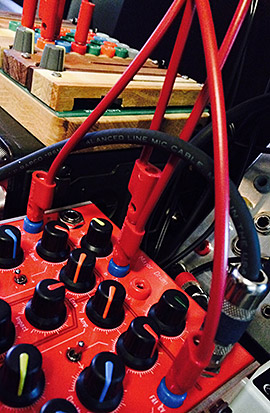

BugBrand banana jack bonanza!

After getting to know the Tetrax Organ, profiled in my last post, I became interested in what other devices used banana jack interfaces for control voltage (CV) modulation. The eurorack standard for modular synthesis is wildly popular, but its buzz drowns out other equally interesting platforms, like the banana-based Buchla and Serge systems.

This research led me to BugBrand, a quirky English manufacturer of both modular synths and desktop formats (who also happens to be a top notch guy, not to be confused with The Bug, who I’ve been following since his first release in 1997, which is based on The Conversation, which is about a sound recordist…talk about circular references…). I had heard great things about, and from, his gear, especially a well-regarded but often-overlooked device called the DRM1 Major Drum. This filled a hole in my gear list: a dedicated all-analog, super-flexible drum synthesizer. And with a Tetrax Organ and a Low Gain Electronics UTL-1/2Â format converter, I could easily drive it from pretty much any source that output CV.

Hell, it even came in red, like my beloved Grendel Drone Commander.

In short, I picked one up, and am thoroughly enjoying it. It mixes well with other gear, especially if I’m rolling all-analog. It overdrives naturally, aesthetically, and quickly, lending itself to aggressive styles, but not limited to them. I especially like the ability to create rising or falling triggered envelopes via the “Bend” feature. Having two trigger inputs (three if you include the big red button) and CV control of both its oscillator and filter are great. I do wish the filter was steeper for more extreme sculpting of the noise generator, but you do get the choice of bandpass or lowpass/highpass (the latter switchable with an internal jumper) via a front-panel switch.

In all my research, though, I never really came across a single piece of media that really dove into its sound design abilities. While its tone can be varied a little based on the strength of the trigger signal it’s fed, it’s a single-voice synth, and no video demo or Soundcloud track really seemed to express its breadth of sound design possibilities.

So, I decided to do something about it.

So, I decided to do something about it.

The sounds in today’s track are entirely made from the BugBrand DRM1. About half of the tracks are sequenced via the EHX 8-Step Program sequencer pedal (including the dubby melodic loop), and the rest are hand-edited, and one track features modulation form the Tetrax Organ’s touch pressure, and another using the Tetrax’s oscillators to drive the DRM1’s oscillator and filter. Effects include some delays, one reverb, and a bunch of high-pass and low-pass filters and EQ’s, with some compression on the output bus.

The sounds all have a very strong flavor, sharing a lot of timbral qualities, regardless of the function they serve in the mix. That can be good or bad, depending on what you’re after. But still, I think it’s impressive that this is all from a device with only one oscillator, one filter, and only three CV inputs. And this thing has a truly massive frequency range: its lowest pure tones drop to at least 20Hz, and it’s pretty easy to get spikes near or above 20kHz!

Pro tip: BugBrand products are tough to get a hold of, as Tom Bug doesn’t hold much inventory at any one time, so when he makes a production run, they sell out in a heartbeat. If you want to get in on Tom Bug’s next manufacturing runs/releases, get on his list.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/186445537″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: analogue, drum, electronic music, modular, music, sound design, synthesis | 1 Comment »

Posted: December 20th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music

The Ciat Lonbarde Tetrax Organ, designed by Peter Blasser.

Many readers know that my day job is as a creative director for interactive installations. I create interfaces for a living, so I’m keenly sensitive to the interfaces of musical devices and software. Some I suffer through because the sound is so amazing, and others I deeply admire in for their immediacy or efficacy.

When I first heard about Peter Blasser and his Ciat Lonbarde brand of wooden electronic instruments, I was instantly captivated. The entry-level Tetrax Organ caught my eye: A stereo, four-voice, touch-sensitive synth made of wood, sliders, knobs, and semi-modular patch points? I had to check this out.

Four barres, four sliders, four knobs, 4 columns of patch points. Its sound is far less symmetrical or simple as its appearance would have you believe.

Peter has been the subject of a short documentary, has multiple brands of instruments that he builds, writes poetry about circuit board layouts, which look like nothing you’ve ever seen before. His instruments are in no way traditional in design or timbre. Two compilations have been made featuring the kinds of sounds these instruments can make.

However, a Ciat Lonbarde instrument’s strangeness and underground/indie hype quickly fades from memory once you use one, for a simple reason: Expressiveness. And a design philosophy that takes a stand, Â and winds up massively differentiated from anything that has come before.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181365218″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The Tetrax Organ, then, is the most affordable Ciat Lonbarde instrument. It’s simple to play, and quite small: Think of it as the Korg Volca Keys of the Ciat Lonbarde milieu. Its electronic guts live visibly in a sandwich of two layers of multi-colored laminated wood. It has four wooden barres [sic], each with a piezoelectric element that makes the barre sensitive to pressure, each controlling an analog triangle core oscillator. Each barre has a coarse pitch slider, and each pair of barres has an additional tuning knob. “Chaos” knobs for how much the oscillators modulate each other, leading up to colored noise. A host of color-coded 4mm banana patch points in the middle provide modulation options aplenty, which respond to standard control voltage (CV) signals; each column of jacks controls one of the barres. You design tones per barre, as well as interactions between the barres as you start to play with its patchbay. It’s lighter than most stompboxes.

A “format jumbler” like the Low-Gain Electronics UTL-4 makes using control voltage with Ciat Lonbarde instruments a snap. Here the Tetrax is being modulated by an EHX 8-Step Program sequencer, using an EHX Clockworks as the master clock, which is also driving a Korg Volca Beats and Volca Bass. This is a really fun setup for improvising!

The Tetrax Organ doesn’t have filter controls, editable envelopes, MIDI, detents on sliders or knobs for neutral or default tuning, or memory for patch storage. There are no LFO’s (that’s what the oscillators and its semi-modular patchbay is for). It doesn’t have a single status LED, either. This means that you need to turn it on and manipulate it. The only controls are the ones you can actually play. It’s direct, encourages exploration, and allows for very happy accidents. These are manifestations of Peter’s philosophies, rendered in PCBs, sassafras, walnut, steel, and plastic.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181395836″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

This means it has a sound all its own, but within its own world. I can produce sounds from chaotic to melodic to percussive, and its purity (and sometimes harshness) of tone holds up very well to heavy effects processing. It can be abrasive or sweet, noisy or mellow, deep or piercing, while having its own supremely unique character. Sonically it has a lot more in common with the so-called “West Coast” synth design philosophy, like the Buchla, embracing unpredictability, unearthly sounds, complex timbres, and nontraditional playing styles. If you don’t like the sound, though, it’s not for you. You can go on quite a sonic journey, but you’ll have a hard time leaving its particular sonic terrain (ahem, so to speak).

But let’s get back to the interface of the Tetrax Organ. Touch triggers the amplitude envelope’s opening; releasing the barre also triggers the envelope, usually in the opposite channel. Pressure on the barres modulates volume and has some ability to sustain notes, like it’s retriggering the envelope, or part of it. This leads to a method of play/performance that’s unlike any other instrument, except perhaps a MIDI ribbon controller. You can perform percussively, with vibrato, by stroking, and more. Expressive but with its own rules set, it’s up to you to develop a playing style that gets what you want out of the Tetrax Organ.

A good interface, even if initially mysterious, is defined by a short learning curve. The Tetrax delivers on this in spades.

There are no labels and no proper manual for the device. Usually that would drive me crazy, but part of the Ciat Lonbarde philosophy and aesthetic is about embracing chaos and chance, and the instructions online are absolutely enough to get started. Even the lack of patch labeling is easy enough to commit to memory: Warm colors are outputs, cool are inputs, and certain colors map to certain parameters (red is oscillator output, green is chaos input, etc.). While not guessable, it’s knowable and (somewhat) repeatable, with a very manageable learning curve. Other Ciat Lonbarde instruments, like the Plumbutter (ostensibly a drum machine, but it’s not) and the Cocoquantus (ostensibly a dual digital delay, but it’s not), have reputations for being more cryptic and mystical (crypstical?), probably due to the sheer number of routing options they have, the outre concepts they embody, and their inability to be classified in any sort of traditional electronic music device category.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181694292″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The Tetrax Organ’s quirkiness, post-modern design, personality, physicality, timbre, and narrow set of features are specifically what makes it unique and enjoyable. As traditional hardware synths are to virtual software instruments in a DAW, so is the Tetrax Organ to an iPad music app: Simpler than it looks, narrowly focused in what it can produce, but its tactility is its deepest joy.

It’s the simplest and least flexible of the Ciat Lonbarde family of instruments, but that’s a good thing. You can unbox it, plug it in (12VDC power cord or 9V battery), and instantly start making sound with it. It’s the perfect way to get into Ciat Lonbarde’s odd world of off-kilter, organic, and unstable sounds, while still being able to play up to four notes of melody (or drumlike sounds) at once. Peter’s a pleasant guy, but very busy; if you want to learn more from other Ciat Lonbarde owners, there is an active subforum dedicated to Ciat Lonbarde instruments on the MuffWiggler modular synth forum.

Nothing else sounds quite like it. Absolutely nothing compares to playing it.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/182470504″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=true&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: ciat lonbarde, interface, music, music 2014 | No Comments »

Posted: December 20th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: found sound objects, music, sound design

A lush nest of sonic discomfort.

Following on my last post, I’ve continued to play around with my recordings of deer antlers through a contact microphone. Today’s sound is almost entirely from that session, with only a handful of synthesized sounds, all triggered by LFOs and other random modulations. The manipulations of the deer antler sounds were done in the very weird, pretty unstable, and utterly unique Gleetchlab application, as well as iZotope Iris, which did an amazing job of figuring out the root frequency of the flute-like and cello-like bowed resonances.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/182406370″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: found object, music, music 2014, sound design | No Comments »

Posted: December 15th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: found sound objects, music, sound design

Most years I host a “white elephant” party: Bring gifts you were given that are pretty bad, re-wrap them, and then you pick from the pile and laugh at the bizarre stuff you unwrap. Last year, I wound up with a pair of deer antlers.

I don’t hunt, yet I have a thing for taxidermy. I have no idea why.

As they sat in my studio, I thought back to an interview I did with Cheryl Leonard for the Sonic Terrain blog a few years ago. I remember her making instruments from limpet shells and other organic objects. Why was I not exploring the sonic possibilities of this strange object on my shelf?

Deer antlers are bone, not hair, so they are riddled with hollow channels, and are extremely tough. The main thing I tried was to explore their resonance, with a cello bow. I had to lay a good amount of rosin on the bow, but they did resonate. The sound is hissy, atonal, but with some pronounced fundamentals and overtones…just not in relationships that one usually considers musical. I used a Barcus Berry 4000 contact microphone and recorded onto a Sound Devices 702 field recorder.

When I hear an interesting sustained sound with too many frequencies, or odd frequency relationships, I usually go to one place to create something musical out of it: iZotope Iris. It’s a very creative tool for making playable virtual instruments out of pretty much any sound. In this case I also used New Sonic Arts’ Granite granular synthesis plugin for several layers. It all sounded very breath-y, like a somewhat melodic whisper. I mixed it with some LFO-driven rhythms in Reason and a bassline and drone from Madrona Labs’ Aalto. It was all put together in Logic Pro X with very few effects, lightly compressed by Cytomic’s The Glue.

Deer antlers, even processed through modern software, aren’t the most flexible or sonically soothing instruments around, but this article can at least serve as a reminder to explore everything around us for its interesting sonic possibilities. You never know what you’ll find.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181708958″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: ambient, drone, found object, music, music 2014, resonance | No Comments »

Posted: November 26th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music, sound design, synthesis

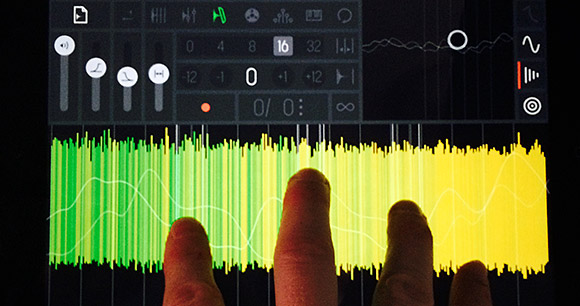

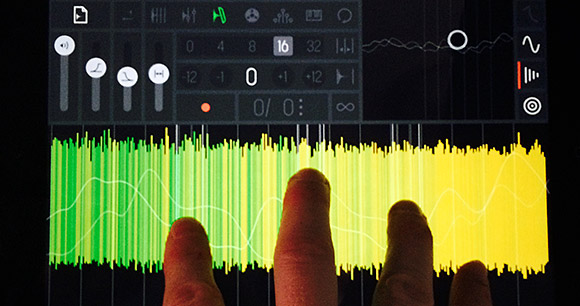

Letting my fingers do the walking, and talking, in Samplr for iOS.

A while back, Sonic State did a neat profile of Alessandro Cortini’s live synth setup for Nine Inch Nails, in which he described his use of a four-track cassette player as a mellotron. He’d record many, many repeating loops, one loop per track, and then use the mixing faders to fly out certain chords or drones. Pretty fun use of old technology.

In playing around with Samplr for iOS, it struck me that it could behave like a mellotron of sorts, too. Sure, Samplr (and other similar apps, like Curtis, csSpectral, and Sector) is great for mashing stuff up in an extreme way, but I decided if I could play it a bit more like a piano.

Since Samplr only slices samples into increments of four, I output a little more than two scales of a synth sound in G# minor. Then it was a simple as loading that sample in, selecting 16 slices, and then playing Samplr as a keyboard.

The results were odd, glitchy, loose, and interesting. I liked that I could hold chords while also dialing in reverb, delay, even playback loop length. The loop points were obvious, but at the right lengths and tempos, they can become rhythmic or simply textural. When playing single melodies, possible by dragging my finger between slices simulated piano runs. Then, inspired by Mr. Cortini’s solo albums, I decided to make a track with samples just from one single synth, played back from Samplr.

Today’s audio clip features a live recording in multiple passes. All of the sounds are from the TAL Bassline101, an amazing emulator of the Roland SH101. I output only two audio files, each with a unique patch but in the same pitch range and scale, and the rest of the variations are from Samplr.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/178303998″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: iPad, music, music 2014, software | No Comments »

Posted: October 27th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music, synthesis

Today’s track is comprised of several ominous improvisations with analog synths: Korg Volca Beats, Korg Volca Bass, Waldorf Pulse +, and Grendel Drone Commander. A couple of virtual analog software synths were also used to round things out in the edit.

Nice to get back into the pure subtractive synthesis world for a whole, in terms of sound design. I need to grow more hands if I’m to tweak this many knobs at once…

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/173187112″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: analogue, audio equipment, music, music 2014 | No Comments »

Posted: October 21st, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music

Desolate, tense, unnerving.

Imagining a largely post-human landscape with a guitar, field recordings of bowed cymbals and rusty steel objects, chromatic steel percussion, and more. Heavily influence by a winter of reading post-apocalyptic fiction novels.

Live drums by Jules König, appropriately recorded in a gritty former sweatshop.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/170806959″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: cinematic, composition, music, music 2014 | No Comments »

Posted: October 7th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music

Lonely, dark, maritime.

[Author’s Note: This fall, I’ll be sharing some music I’ve worked on in 2014. A little different, but still in keeping with the concept of this blog. Hope you enjoy the change of pace for a little bit!]

I decided to try to write something in 3/4 time, which I don’t do that often. It’s so easy to make 3/4 time sound like a waltz, all poncy and upper-crust. Or, at worst, a twee indie film about awkward romance, especially with instruments that are traditionally for that time signature, like accordions. So, I tried to create a track in 3/4 that had a mix of menace and whimsy.Â

This composition features a strange arrangement of instruments: Harmonium through a distortion pedal, piano, tiny electronic percussion, timables, glockenspiel, double bass, and harp.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/170801469″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: cinematic, composition, music, music 2014 | No Comments »

![Want a challenge? Try to play back interface sounds on the show floor at CES. [Intel Booth, CES 2012.]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-03.jpg)

![This prototype "factory of the future" had to have its sound design elevated over the sounds of compressors and feeders to ensure zero defects. [GlaxoSmithKline, London, England]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-05.jpg)

![This lobby installation started with abstract chirps, bloops, and blurps, but became quite musical after the client felt the sci-fi sounds were far too alienating. [Quintiles corporate lobby, Raleigh NC]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-01.jpg)

![This installation had no sound at all, despite our best attempts and deepest desires. The environment was too tall, too acoustically bright, and too loud. Sometimes it just doesn't work. [Genentech, South San Francisco, CA]](https://noisejockey.net/blog/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/musicalSDI-04.jpg)

So, I decided to do something about it.

So, I decided to do something about it.