Posted: August 31st, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music, news

Today, I’ve got two exciting announcements to share!

First, there is a new subdomain and site that tracks my musical output: music.noisejockey.net. This blog will remain focused on sound design, audio technique, and field recording, whether the final output or usage is musical or not.

Second, I’m releasing my first full-length LP, titled Dissolver, on September 14. It will be available as a digital download on Bandcamp, Amazon, iTunes, and Google Play. Read the full announcement, and listen to a four-minute album teaser.

Watch this space and my Twitter feed for more!

| No Comments »

Posted: July 17th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music, sound design

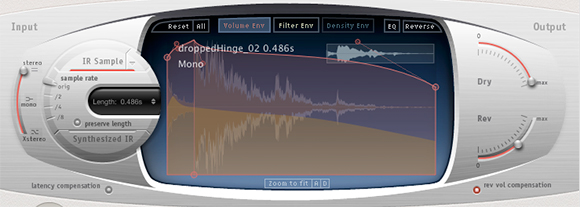

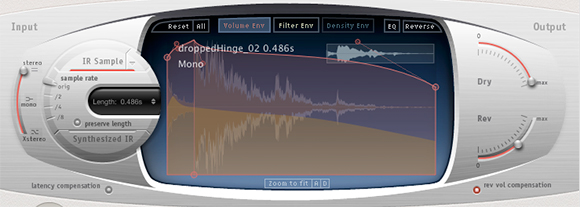

Sure, it’s fun to use long, non-reverb sounds as impulse responses…but what about short, percussive ones?

Convolution reverbs have been a staple of audio post-production for a good while, but like most tools of any type, I prefer to force tools into unintentional uses.

While I am absolutely not the first person to use something other than an actual spatial, reverb-oriented impulse response – bowed cymbals are amazing impulse responses, by the way – I hadn’t really looked into using very short, percussive impulse responses until recently. I mean, it’s usually short percussive sounds you’re processing through the convolution reverb. I found that it can add an overtone to a sound that can be pretty unique. Try it sometime!

(Coincidentally, today Diego Stocco’s is promoting his excellent Rhythmic Convolutions, a whole collection of impulse responses meant for just these creative purposes. Go check it out!)

Today’s sample is in three parts. First, a very bland percussion track. Then, the sound of a rusty hinge dropped from about one foot onto a rubber mat, recorded with my trusty Sony PCM-D50 field recorder. Then, the same percussion track through Logic Pro’s Space Designer (Altiverb or any other convolution reverb will do, of course) using the dropped hinge sound as an impulse response. It adds a sort of distorted gated reverb, adding some grit, clank, and muscle to an otherwise pretty weak sound.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/214427372″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: convolution, digital audio, reverb, software, sound design | No Comments »

Posted: July 11th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music, sound design, synthesis

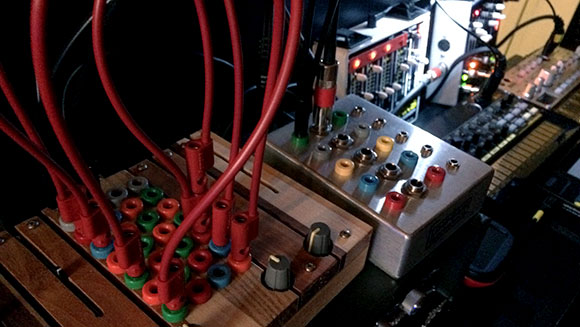

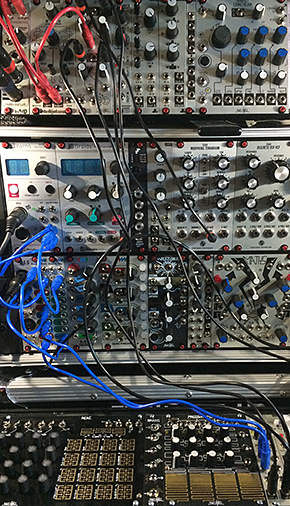

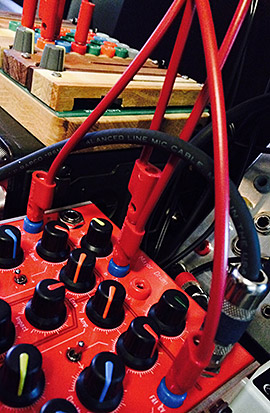

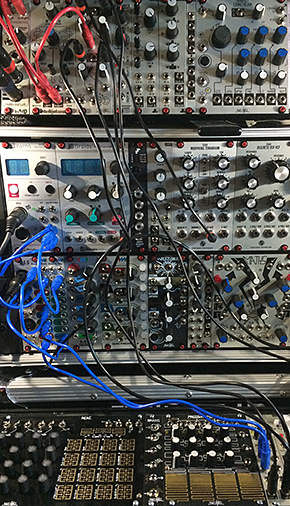

The joys of knobs. And patch points. And empty bank accounts.

While this may be old news to my followers on Soundcloud, Twitter and Instagram, I’ve configured my first Eurorack-format modular synthesizer. These cabled amalgamations of faceplates, cables, circuits, and glowing LEDs are desirable, fetishized, addictive, and steeped in history. But, really, they’re just tools.

But what tools they are. Modular synthesizers are no longer relegated to the dustbin of history, nor an underground elite (as well documented in the excellent documentary, I Dream of Wires). They have come roaring back, arguably leading the way in technical synthesis innovation, and are a commonplace instrument in many studios. This boom has even gotten the heavyweights of mass market synthesizers, like Roland, to (re)release Eurorack modules, and pop musicians like Martin Gore to release all-modular electronic albums.

But what tools they are. Modular synthesizers are no longer relegated to the dustbin of history, nor an underground elite (as well documented in the excellent documentary, I Dream of Wires). They have come roaring back, arguably leading the way in technical synthesis innovation, and are a commonplace instrument in many studios. This boom has even gotten the heavyweights of mass market synthesizers, like Roland, to (re)release Eurorack modules, and pop musicians like Martin Gore to release all-modular electronic albums.

Everyone’s path to modular synthesis is different, as is mine. But why did I go modular? How did I even know where to begin? And how can I hope to stem the addictive nature of constantly adding low-cost modules, which leads it to be known as “Eurocrack?”

Embrace Limitations

It’s tempting to just buy flavor-of-the-month new products, but that way lies financial ruin and a studio full of stuff you don’t use. The way to stem the financial bleed and random module selection is to place limitations on the process. For me, the limitations were as follows.

- I’ve got a significant investment in existing software and hardware that I want to honor and leverage, not duplicate. I’m designing an additional instrument, not building a new studio.

- I have limited physical space in my home studio. Therefore my case will be on the small side, and that will enforce limits on the number of modules I can purchase.

- I will “version” the modular synth and roadmap it, as if I was designing an actual instrument or a piece of software. I will buy modules in two initial rounds: v0.5 to instantiate the most basic system to ensure that the workflow and gestalt of modular synthesis does actually speak to me, and then a v1.0 that I will live with for a year. Only after user testing – my own, of course – can I roadmap a meaningful path to a v1.5, v2.0, and so on.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/209374238″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Everything’s a Design Problem

I’ve spent my career breaking down everything, from human relationship challenges to sound design, as a set of design problems. This helps frame the real problem so that solutions are more meaningful. So, I asked myself: What’s the problem I’m trying to solve, or am I just lusting after gear? (Spoiler: It’s both!)

- My current system lacked in two key areas: complex modulation options and the ability to support serendipity. My existing tools didn’t have much in the way for allowing for happy accidents, randomness, and cross-modulated signals and patterns of control. When my most interesting and complex synthesized rhythms and timbres I was creating were coming from Propellerhead Reason during my morning bus commute, I knew something was missing in my main studio.

- Software is an expense, hardware is an investment. Software suffers from instability and, over the long haul, the danger of becoming incompatible that many hardware units do not.

- I’ve already been enjoying workflow of using external hardware as sound sources and then post-processing them digitally, or the other way around.

With the above considerations, the idea of a flexible, modulation-rich instrument to add to the stable seemed to make sense.

Plus: Blinky lights.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/204513759″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Create Rules of Engagement

Modular synths are, well, modular: Flexibility is what they’re all about. But you are building your own instrument. Without a sense for what you want to accomplish, you’ll overspend and not get what you really need…and, more dangerously, you won’t know when you should stop buying modules. Most of us don’t have the disposable income to buy modules willy-nilly.

Here were my rules of engagement for assembling my modular synth. These will change over time, but it helped me understand what the first iteration of this instrument would be. I wrote these down and re-read them any time I started to think about adding a new module.

- No analog oscillators. While that may seem against conventional modular wisdom, I have a total of ten analog oscillators across four other devices. I’ve got this covered. Go for something really unusual as a sound source.

- No effects. I know that even if I monitor a track with effects on, I always record dry and have effects as plugins or rendered to separate tracks. I use tons of plugins and stompboxes: I have effects covered already.

- Go nuts with modulation. Having enough tools to generate and modify clock signals and control voltages will be critical, because I don’t have digital tools that excel at this. Get more modules that control modulation than produce sound (or, ideally, ones that can do both).

- Don’t forget the DAW. I’ve got a significant investment in a computer-based audio workstation that should be leveraged, so ensuring that modulation and clock signals can drive the modular was critical.

- Embrace multi-tracking. Look at the modular as a sound design station, instrument, or voice, not as a complete studio. Get enough expressive options to do drones, melodies, and unusual percussion…but I don’t have to do all these things at once. That also means no more than 2 channels in or out of the modular synth.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/204871725″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The Result

You can read all the key specs on my modular synth, its output and effects subrack (told you I’d break some rules!), and its “controller skiff” on ModularGrid.net, so I won’t geek out about it here. So far, though, so good.

- There’s nothing mysterious about putting a modular together or how it’s used, as long as you have a good grasp of signal flow inside a typical synthesizer. It doesn’t really take any other technical skills other than using a screwdriver, reading directions, and doing simple math around power consumption.

- I’ve got solid sync with my DAW.

- I’ve got an instrument that can do things none of my other instruments can, and vice-versa.

- I’ve got methods to interface with effects pedals, external semi-modular instruments (even with different interconnects), my DAW, and even my iPad. It’s deeply integrated into the rest of my studio.

- It’s small. Full, but small. It’s even able to be self-contained if I decide to embrace limitations and create sounds or music only with this instrument outside of my studio or otherwise away from my DAW, even with my vintage Roland TR-606 drum machine.

- It’s capable of percussion, melody, and drones that can modulate in complex and random ways over seconds or many minutes.

- Modular users have a reputation for noodling and sound designing, but never actually completing songs or projects. It’s like an aural sandbox. The satisfaction of signal routing is autotellic: It’s its own reward, constant discovery and following or rejecting conventional wisdom. It’s also extremely meditative once you’re past the initial learning curve.

- I’ve already broken the “no effects” rule, but only with modules that can be “self-patched” and act as sound sources in their own right.

- Even having only purchased digital oscillator modules, analog modulators like LFO’s can often be used as analog oscillators when they are pushed into the audible range, as can filters that self-oscillate when their resonance is set high. I even wound up with four analog oscillators without knowing it.

- Once you realize that anything can be routed into anything, all synthesis rules go out the window. LFOs and filters can be oscillators, as mentioned above, but clocks can be triggers, envelopes can be clocks, envelopes can be LFOs, audio amplitude can modulate anything…that’s the mind implosion and creativity that modular synthesis brings.

Over time, will I jettison older gear and go all Eurorack? Will I dispense with the computer entirely for making music? Probably not. But I’m sure my system will slowly expand, change, and evolve with my interests, just as I’ve shifted from oils to acrylics to pastels to pencils to pixels in my visual arts career. The initial rules I started with will morph, change, get relaxed, and get updated. My initial configurations has gaps and weaknesses, but nothing’s perfect. And now I’m good to go with a new palette of sonic colors.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have field recordings to run through my modular.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/212269329″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

| 5 Comments »

Posted: June 8th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music

The Stylophone, as most readers of this blog probably know, is a musical toy made famous by David Bowie’s use of it in the track Space Oddity. I own one but honestly, it’s kind of hard to play, and even harder to fit into a mix. Playing evenly with a stylus takes practice and its tones are harsh and nasal.

But it’s 2014. Anything can be made to sound like anything.

I picked up a Korg Mini Kaoss Pad 2 on a whim, and like Korg’s Volca and Monotron range, it’s not great…but it’s an amazing value for the price. What it lacks in configurability and customization it makes up for in expressiveness, immediacy, and convenience. In playing with its onboard loopers – especially the Overdub Looper effect – I realized that I’d never heard Stylophones playing chords. Something new to try…

So, bear with me on how today’s piece came about. The Stylophone’s leftmost tone switch position gives some low-end growl below the E key, and recording it via the headphone out smooths the sound, compared to miking the tiny onboard speaker. I set the MiniKaoss Pad’s Overdub Looper to a certain BPM and build a series of chords on the Stylophone, and used the Mini Kaoss Pad 2’s ability to record directly to an onboard microSD card. The loop points are obvious but intentional and rhythmic, creating an interesting sound, not unlike the Samplr snippet I posted a few months back.

Then I ran that through Michael Norris‘ Spectral Blur plugin to make a hazy, dreamlike wash that communicated what I wanted. Everything else then fell into place, including a TR-606 run through a vintage mono cassette deck, my beloved BugBrand DRM-1, and one of my favorite software synths, TAL Bassline 101.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/209445429″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: looping, music, music 2014, sampling | No Comments »

Posted: January 19th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music, synthesis

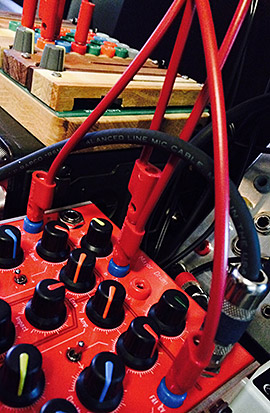

BugBrand banana jack bonanza!

After getting to know the Tetrax Organ, profiled in my last post, I became interested in what other devices used banana jack interfaces for control voltage (CV) modulation. The eurorack standard for modular synthesis is wildly popular, but its buzz drowns out other equally interesting platforms, like the banana-based Buchla and Serge systems.

This research led me to BugBrand, a quirky English manufacturer of both modular synths and desktop formats (who also happens to be a top notch guy, not to be confused with The Bug, who I’ve been following since his first release in 1997, which is based on The Conversation, which is about a sound recordist…talk about circular references…). I had heard great things about, and from, his gear, especially a well-regarded but often-overlooked device called the DRM1 Major Drum. This filled a hole in my gear list: a dedicated all-analog, super-flexible drum synthesizer. And with a Tetrax Organ and a Low Gain Electronics UTL-1/2Â format converter, I could easily drive it from pretty much any source that output CV.

Hell, it even came in red, like my beloved Grendel Drone Commander.

In short, I picked one up, and am thoroughly enjoying it. It mixes well with other gear, especially if I’m rolling all-analog. It overdrives naturally, aesthetically, and quickly, lending itself to aggressive styles, but not limited to them. I especially like the ability to create rising or falling triggered envelopes via the “Bend” feature. Having two trigger inputs (three if you include the big red button) and CV control of both its oscillator and filter are great. I do wish the filter was steeper for more extreme sculpting of the noise generator, but you do get the choice of bandpass or lowpass/highpass (the latter switchable with an internal jumper) via a front-panel switch.

In all my research, though, I never really came across a single piece of media that really dove into its sound design abilities. While its tone can be varied a little based on the strength of the trigger signal it’s fed, it’s a single-voice synth, and no video demo or Soundcloud track really seemed to express its breadth of sound design possibilities.

So, I decided to do something about it.

So, I decided to do something about it.

The sounds in today’s track are entirely made from the BugBrand DRM1. About half of the tracks are sequenced via the EHX 8-Step Program sequencer pedal (including the dubby melodic loop), and the rest are hand-edited, and one track features modulation form the Tetrax Organ’s touch pressure, and another using the Tetrax’s oscillators to drive the DRM1’s oscillator and filter. Effects include some delays, one reverb, and a bunch of high-pass and low-pass filters and EQ’s, with some compression on the output bus.

The sounds all have a very strong flavor, sharing a lot of timbral qualities, regardless of the function they serve in the mix. That can be good or bad, depending on what you’re after. But still, I think it’s impressive that this is all from a device with only one oscillator, one filter, and only three CV inputs. And this thing has a truly massive frequency range: its lowest pure tones drop to at least 20Hz, and it’s pretty easy to get spikes near or above 20kHz!

Pro tip: BugBrand products are tough to get a hold of, as Tom Bug doesn’t hold much inventory at any one time, so when he makes a production run, they sell out in a heartbeat. If you want to get in on Tom Bug’s next manufacturing runs/releases, get on his list.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/186445537″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: analogue, drum, electronic music, modular, music, sound design, synthesis | 1 Comment »

Posted: January 17th, 2015 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music, news, synthesis

This blog is nearly six years old, and it’s time for a facelift!

You might notice that there is a new logo in the header of the website, and a few new fonts. Thanks to the design machinations of GergWerk, Noise Jockey now has a new visual identity and design system. Many thanks to Gerg and his hard werk…especially given that his client, your humble author, is a picky designer himself.

Expect a few visual tweaks over the next few weeks as the new identity works its way more fully into the website and other channels, like my Twitter and Soundcloud accounts.

In honor of the first visual change here since launch, I figured I’d post a little ditty that referred back to my first post, back in 2009: A short piece done on the Casio Magic Sound Dial SA-40 toy keyboard. It was multi-tracked, miked with Ye Olde Shure SM57, and run through a Red Panda Particle pedal as well as a few plug-in effects.

Here’s to new beginnings!

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/186563283″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

| No Comments »

Posted: December 20th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: gear, music

The Ciat Lonbarde Tetrax Organ, designed by Peter Blasser.

Many readers know that my day job is as a creative director for interactive installations. I create interfaces for a living, so I’m keenly sensitive to the interfaces of musical devices and software. Some I suffer through because the sound is so amazing, and others I deeply admire in for their immediacy or efficacy.

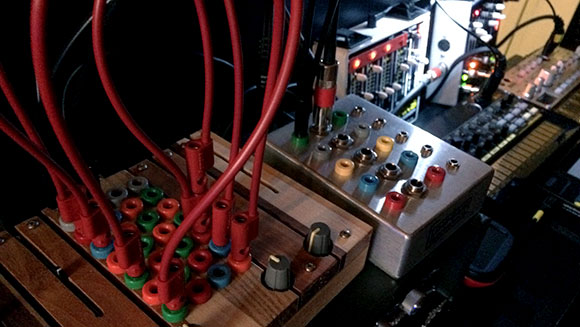

When I first heard about Peter Blasser and his Ciat Lonbarde brand of wooden electronic instruments, I was instantly captivated. The entry-level Tetrax Organ caught my eye: A stereo, four-voice, touch-sensitive synth made of wood, sliders, knobs, and semi-modular patch points? I had to check this out.

Four barres, four sliders, four knobs, 4 columns of patch points. Its sound is far less symmetrical or simple as its appearance would have you believe.

Peter has been the subject of a short documentary, has multiple brands of instruments that he builds, writes poetry about circuit board layouts, which look like nothing you’ve ever seen before. His instruments are in no way traditional in design or timbre. Two compilations have been made featuring the kinds of sounds these instruments can make.

However, a Ciat Lonbarde instrument’s strangeness and underground/indie hype quickly fades from memory once you use one, for a simple reason: Expressiveness. And a design philosophy that takes a stand, Â and winds up massively differentiated from anything that has come before.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181365218″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The Tetrax Organ, then, is the most affordable Ciat Lonbarde instrument. It’s simple to play, and quite small: Think of it as the Korg Volca Keys of the Ciat Lonbarde milieu. Its electronic guts live visibly in a sandwich of two layers of multi-colored laminated wood. It has four wooden barres [sic], each with a piezoelectric element that makes the barre sensitive to pressure, each controlling an analog triangle core oscillator. Each barre has a coarse pitch slider, and each pair of barres has an additional tuning knob. “Chaos” knobs for how much the oscillators modulate each other, leading up to colored noise. A host of color-coded 4mm banana patch points in the middle provide modulation options aplenty, which respond to standard control voltage (CV) signals; each column of jacks controls one of the barres. You design tones per barre, as well as interactions between the barres as you start to play with its patchbay. It’s lighter than most stompboxes.

A “format jumbler” like the Low-Gain Electronics UTL-4 makes using control voltage with Ciat Lonbarde instruments a snap. Here the Tetrax is being modulated by an EHX 8-Step Program sequencer, using an EHX Clockworks as the master clock, which is also driving a Korg Volca Beats and Volca Bass. This is a really fun setup for improvising!

The Tetrax Organ doesn’t have filter controls, editable envelopes, MIDI, detents on sliders or knobs for neutral or default tuning, or memory for patch storage. There are no LFO’s (that’s what the oscillators and its semi-modular patchbay is for). It doesn’t have a single status LED, either. This means that you need to turn it on and manipulate it. The only controls are the ones you can actually play. It’s direct, encourages exploration, and allows for very happy accidents. These are manifestations of Peter’s philosophies, rendered in PCBs, sassafras, walnut, steel, and plastic.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181395836″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

This means it has a sound all its own, but within its own world. I can produce sounds from chaotic to melodic to percussive, and its purity (and sometimes harshness) of tone holds up very well to heavy effects processing. It can be abrasive or sweet, noisy or mellow, deep or piercing, while having its own supremely unique character. Sonically it has a lot more in common with the so-called “West Coast” synth design philosophy, like the Buchla, embracing unpredictability, unearthly sounds, complex timbres, and nontraditional playing styles. If you don’t like the sound, though, it’s not for you. You can go on quite a sonic journey, but you’ll have a hard time leaving its particular sonic terrain (ahem, so to speak).

But let’s get back to the interface of the Tetrax Organ. Touch triggers the amplitude envelope’s opening; releasing the barre also triggers the envelope, usually in the opposite channel. Pressure on the barres modulates volume and has some ability to sustain notes, like it’s retriggering the envelope, or part of it. This leads to a method of play/performance that’s unlike any other instrument, except perhaps a MIDI ribbon controller. You can perform percussively, with vibrato, by stroking, and more. Expressive but with its own rules set, it’s up to you to develop a playing style that gets what you want out of the Tetrax Organ.

A good interface, even if initially mysterious, is defined by a short learning curve. The Tetrax delivers on this in spades.

There are no labels and no proper manual for the device. Usually that would drive me crazy, but part of the Ciat Lonbarde philosophy and aesthetic is about embracing chaos and chance, and the instructions online are absolutely enough to get started. Even the lack of patch labeling is easy enough to commit to memory: Warm colors are outputs, cool are inputs, and certain colors map to certain parameters (red is oscillator output, green is chaos input, etc.). While not guessable, it’s knowable and (somewhat) repeatable, with a very manageable learning curve. Other Ciat Lonbarde instruments, like the Plumbutter (ostensibly a drum machine, but it’s not) and the Cocoquantus (ostensibly a dual digital delay, but it’s not), have reputations for being more cryptic and mystical (crypstical?), probably due to the sheer number of routing options they have, the outre concepts they embody, and their inability to be classified in any sort of traditional electronic music device category.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181694292″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

The Tetrax Organ’s quirkiness, post-modern design, personality, physicality, timbre, and narrow set of features are specifically what makes it unique and enjoyable. As traditional hardware synths are to virtual software instruments in a DAW, so is the Tetrax Organ to an iPad music app: Simpler than it looks, narrowly focused in what it can produce, but its tactility is its deepest joy.

It’s the simplest and least flexible of the Ciat Lonbarde family of instruments, but that’s a good thing. You can unbox it, plug it in (12VDC power cord or 9V battery), and instantly start making sound with it. It’s the perfect way to get into Ciat Lonbarde’s odd world of off-kilter, organic, and unstable sounds, while still being able to play up to four notes of melody (or drumlike sounds) at once. Peter’s a pleasant guy, but very busy; if you want to learn more from other Ciat Lonbarde owners, there is an active subforum dedicated to Ciat Lonbarde instruments on the MuffWiggler modular synth forum.

Nothing else sounds quite like it. Absolutely nothing compares to playing it.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/182470504″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=true&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: ciat lonbarde, interface, music, music 2014 | No Comments »

Posted: December 20th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: found sound objects, music, sound design

A lush nest of sonic discomfort.

Following on my last post, I’ve continued to play around with my recordings of deer antlers through a contact microphone. Today’s sound is almost entirely from that session, with only a handful of synthesized sounds, all triggered by LFOs and other random modulations. The manipulations of the deer antler sounds were done in the very weird, pretty unstable, and utterly unique Gleetchlab application, as well as iZotope Iris, which did an amazing job of figuring out the root frequency of the flute-like and cello-like bowed resonances.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/182406370″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: found object, music, music 2014, sound design | No Comments »

Posted: December 15th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: found sound objects, music, sound design

Most years I host a “white elephant” party: Bring gifts you were given that are pretty bad, re-wrap them, and then you pick from the pile and laugh at the bizarre stuff you unwrap. Last year, I wound up with a pair of deer antlers.

I don’t hunt, yet I have a thing for taxidermy. I have no idea why.

As they sat in my studio, I thought back to an interview I did with Cheryl Leonard for the Sonic Terrain blog a few years ago. I remember her making instruments from limpet shells and other organic objects. Why was I not exploring the sonic possibilities of this strange object on my shelf?

Deer antlers are bone, not hair, so they are riddled with hollow channels, and are extremely tough. The main thing I tried was to explore their resonance, with a cello bow. I had to lay a good amount of rosin on the bow, but they did resonate. The sound is hissy, atonal, but with some pronounced fundamentals and overtones…just not in relationships that one usually considers musical. I used a Barcus Berry 4000 contact microphone and recorded onto a Sound Devices 702 field recorder.

When I hear an interesting sustained sound with too many frequencies, or odd frequency relationships, I usually go to one place to create something musical out of it: iZotope Iris. It’s a very creative tool for making playable virtual instruments out of pretty much any sound. In this case I also used New Sonic Arts’ Granite granular synthesis plugin for several layers. It all sounded very breath-y, like a somewhat melodic whisper. I mixed it with some LFO-driven rhythms in Reason and a bassline and drone from Madrona Labs’ Aalto. It was all put together in Logic Pro X with very few effects, lightly compressed by Cytomic’s The Glue.

Deer antlers, even processed through modern software, aren’t the most flexible or sonically soothing instruments around, but this article can at least serve as a reminder to explore everything around us for its interesting sonic possibilities. You never know what you’ll find.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/181708958″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: ambient, drone, found object, music, music 2014, resonance | No Comments »

Posted: November 26th, 2014 | Author: Nathan | Filed under: music, sound design, synthesis

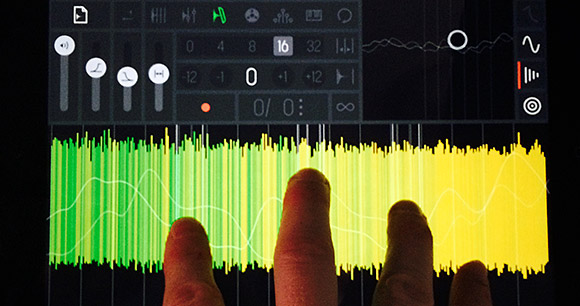

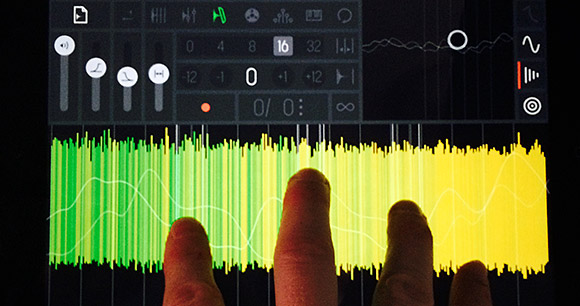

Letting my fingers do the walking, and talking, in Samplr for iOS.

A while back, Sonic State did a neat profile of Alessandro Cortini’s live synth setup for Nine Inch Nails, in which he described his use of a four-track cassette player as a mellotron. He’d record many, many repeating loops, one loop per track, and then use the mixing faders to fly out certain chords or drones. Pretty fun use of old technology.

In playing around with Samplr for iOS, it struck me that it could behave like a mellotron of sorts, too. Sure, Samplr (and other similar apps, like Curtis, csSpectral, and Sector) is great for mashing stuff up in an extreme way, but I decided if I could play it a bit more like a piano.

Since Samplr only slices samples into increments of four, I output a little more than two scales of a synth sound in G# minor. Then it was a simple as loading that sample in, selecting 16 slices, and then playing Samplr as a keyboard.

The results were odd, glitchy, loose, and interesting. I liked that I could hold chords while also dialing in reverb, delay, even playback loop length. The loop points were obvious, but at the right lengths and tempos, they can become rhythmic or simply textural. When playing single melodies, possible by dragging my finger between slices simulated piano runs. Then, inspired by Mr. Cortini’s solo albums, I decided to make a track with samples just from one single synth, played back from Samplr.

Today’s audio clip features a live recording in multiple passes. All of the sounds are from the TAL Bassline101, an amazing emulator of the Roland SH101. I output only two audio files, each with a unique patch but in the same pitch range and scale, and the rest of the variations are from Samplr.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/178303998″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Tags: iPad, music, music 2014, software | No Comments »

But what tools they are. Modular synthesizers are no longer relegated to the dustbin of history, nor an underground elite (as well documented in the excellent documentary,

But what tools they are. Modular synthesizers are no longer relegated to the dustbin of history, nor an underground elite (as well documented in the excellent documentary,

So, I decided to do something about it.

So, I decided to do something about it.